Home-made Sour Cream Butter

A recipe for self-made sour cream butter is at the same time a recipe for butter, crème fraîche and for buttermilk. I am a big fan of ice-cold buttermilk in summer and I love to cook with crème fraîche. Unfortunately, both products are hard to get in Sofia. Only the German supermarkt Hit sells them, and they are often sold out. Making butter at home makes that shortage a little bit easier to live with.

Most butter sold in the supermarket is sweet cream butter made without additional lacto acid bacteriae (also known as lactobacillales), and --- to be honest --- this butter is usually the better choice for cooking because it coagulates less. Mounting a sauce with butter or preparing a sauce hollandaise will usually work better with sweet cream butter.

No matter whether you take sweet or sour cream, the principle is always the same. You whip (or churn) butter until it separates into liquid buttermilk with almost no fat and butter with about 80 percent fat. The base product makes all the difference. It is sweet cream for sweet cream butter and crème fraîche for sour cream butter.

You can, of course, buy the crème fraîche in the supermarkt but that will make for a pretty expensive butter. With just a little patience you can produce your own crème fraîche from regular whipping cream and a little bit of buttermilk, simple and a lot cheaper.

Ingredients

For about 350 g butter and 750 ml buttermilk.

- 1 l whipping cream

- 100 ml butter mil

- 1 l ice water

Preparation

About 10 minutes for preparation, 48 hours rest time.

- Mix the cream with the buttermilk in a closed vessel and let it sit for about 24 hours at 25-30 °C. Do not move! Do not stir!

- After 24 hours the cream has significantly thickened. What you see in front of you is simply crème fraîche. After another 24 hours in the fridge, the crème fraîche is now firm enough to cut with a knife or spoon.

- Whip the crème fraîche in a closed vessel at maximum speed. The cream will at first become firmer. After a couple of minutes you can see yellowish traces of fat until the cream finally separates into butter and buttermilk.

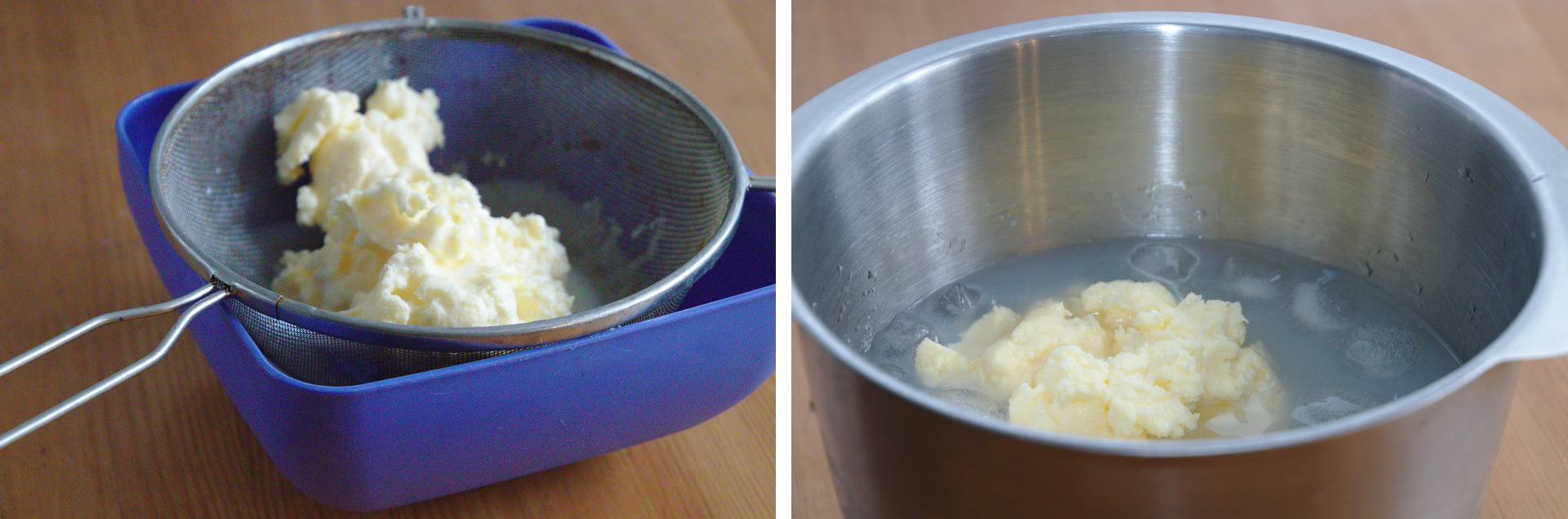

- Pour everything into a sieve catching the buttermilk. Break the lump of butter into smaller pieces, wash them in ice water and drain.

By the way, if you replace the cream with milk, you will produce soured milk instead of crème fraîche. You cannot make butter from soured milk but it is a delicious alternative to yoghurt.

Some more hints:

On the images I have used a food processor. At the end, however, when the cream separates into buttermilk and butter, it squirts terribly. Even covering the bowl will not prevent a big, big mess in your kitchen, and you will lose a lot of delicate buttermilk. Better use a closed blender and work in multiple stages if the blender vessel is too small.

You can let the crème fraîche ripen in the fridge for a couple of days, longer than 24 hours. It will become just a little firmer and sourer because the lactobacillales will continue metabolizing lactose into lactic acid, only a whole lot slower than at room temperature.

You can probably process the crème fraîche immediately into butter, without letting it thicken in the fridge. You should, however, cool it down long enough so that the butter is cold and firm enough for washing. And, by the way, stirring the crème fraîche wil also not hurt the butter. Only the crème fraîche will be less firm but the bacteriae couldn't care less.

You can replace the buttermilk with the same amount of crème fraîche or sour cream. It will be much more expensive but will work just as well, as long as the product you use is not pasteurized, so that the bacteriae are still alive. I would recommend against kefir, although this will depend on the exact kind of kefir you have.

You will read in many instructions that only untreated milk ferments. That is not true. Untreated milk and likewise cream made from untreated milk will ferment without help because it still contains live lacto acid bacteriae. Pasteurized milk needs an addition of buttermilk (or other non-pasteurized sour milk products). That will also work with ultra-high-temperature cream or maybe even with milk replacements based on soy, although I doubt that you can process soy cream into butter. Something similar to crème fraîche should be feasible, however.

Likewise, you often read that the vessel used for the fermentation should be open or only loosely closed, so that lacto acid bacteriae from the air can find their way into the cream. While it is not completely unlikely that a couple of lactobacillales may really find a new home in your cream, this effect is neglectible because there is no shortage of bacteriae in the buttermilk or crème fraîche that you have added to the cream.

Lactobacillales only need water and the enzyme lactase for metabolizing lactose into lactic acid, and they can find all that in cream. They neither need oxygene from the air and can perfectly make do without competitors like acetic acid bacteriae, yeasts, or mold spores. Quite the contrary is true! The other product of the lactobacillales' metabolism is carbon dioxide CO2 that --- being heavier than air --- creates a protection layer on top of the cream, preventing the population with other, undesired micro organisms.

And Why Is Butter Yellow And Milk White?

My 4-year-old son asked me that question the other day while eating cereals with milk for breakfast. A good question.

The yellowish color of butter is easy to explain. A cow's typical diet consists of a lot of grass and other plants containing carotinoids, a group of fat-soluble pigments ranging in color from yellow to red. The fat in milk and liquid cream occurs in the form of microscopic globules. Whipping the cream destroys these globules and the butterfat lumps together showing its original, often yellowish color.

That being said, it should be clear that butter is actually not always yellow. At times, the cows are fed without fresh food, and there are no carotinoides in the milk fat and hence the butter is mostly white. Industrially produced butter is therefore often dyed, at least in those countries where consumers expect butter to be yellow.

And why is milk white and not yellow? Milk is a stable emulsion of butterfat in a transparent liquid, the so-called milk plasma. This milk plasma is essentially water with the water-soluble substances of the milk.

When the light travels through the milk, the butterfat globules cause a refraction of the light waves in all directions creating light of all wave-lengths, that is white light. You know that from the bubbles in your bath. An individual bubble is transparent. But the multitude of little bubbles refract the light and diffuse it in all directions so that the foam is white. The white color of the milk has the same cause only that the bubbles are a lot smaller.

Leave a comment

Giving your email address is optional. But please keep in mind that you cannot get a notification about a response without a valid email address. The address will not be displayed with the comment!